Team communication frequency as a proxy to discovery/delivery health

For this massive release, the teams had been working intensely for consecutive sprints to meet an important milestone for the business. There was no way around this date but we had managed to negotiate the details of what was to be delivered. Regardless, it was a lot.

Things didn’t run smoothly nor equally for the teams. Delivery hadn’t been thoroughly planned nor accompanied, cross-team dependencies hadn’t been mapped or coordinated. Much planning detail was left out as people were subject to a lot of context switch from different cognitive domains and the deadline was tight for the amount of required work.

More reasons were identified during our delivery retrospective. To me, it was a good example of the Swiss Cheese Model in action in terms of software delivery.

As we moved closer to the release date, I noticed that communication was picking up in various Slack channels between team members – within and with adjacent teams.

Some of it was about aligning expectations to get some dependencies delivered, yet much of it was requesting clarification on specificities that were being implemented.

It was kind of a wild thing to see the stream of (sometimes recurring) questions, doubts and confusion picking up pace as teams were merging their work together or getting feedback from various stakeholders as they deployed their work.

To what extent can communication frequency and volume be a health proxy when it comes to delivery success?

This thought came from reading the following line from the book’s 2nd:

Fast flow requires restricting communication between teams. Team collaboration is important for gray areas of development, where discovery and expertise is needed to make progress. But in areas where execution prevails – not discovery – communication becomes an unnecessary overhead.

Restricting team communication? Surely that’s bad.. But giving it a second thought, teams should indeed be communicating less when they have a good understanding of what needs to be delivered, right? It’s not that we’re suppressing their communication. It’s that a healthy delivery should imply less communication at some point of the SDLC, if done correctly.

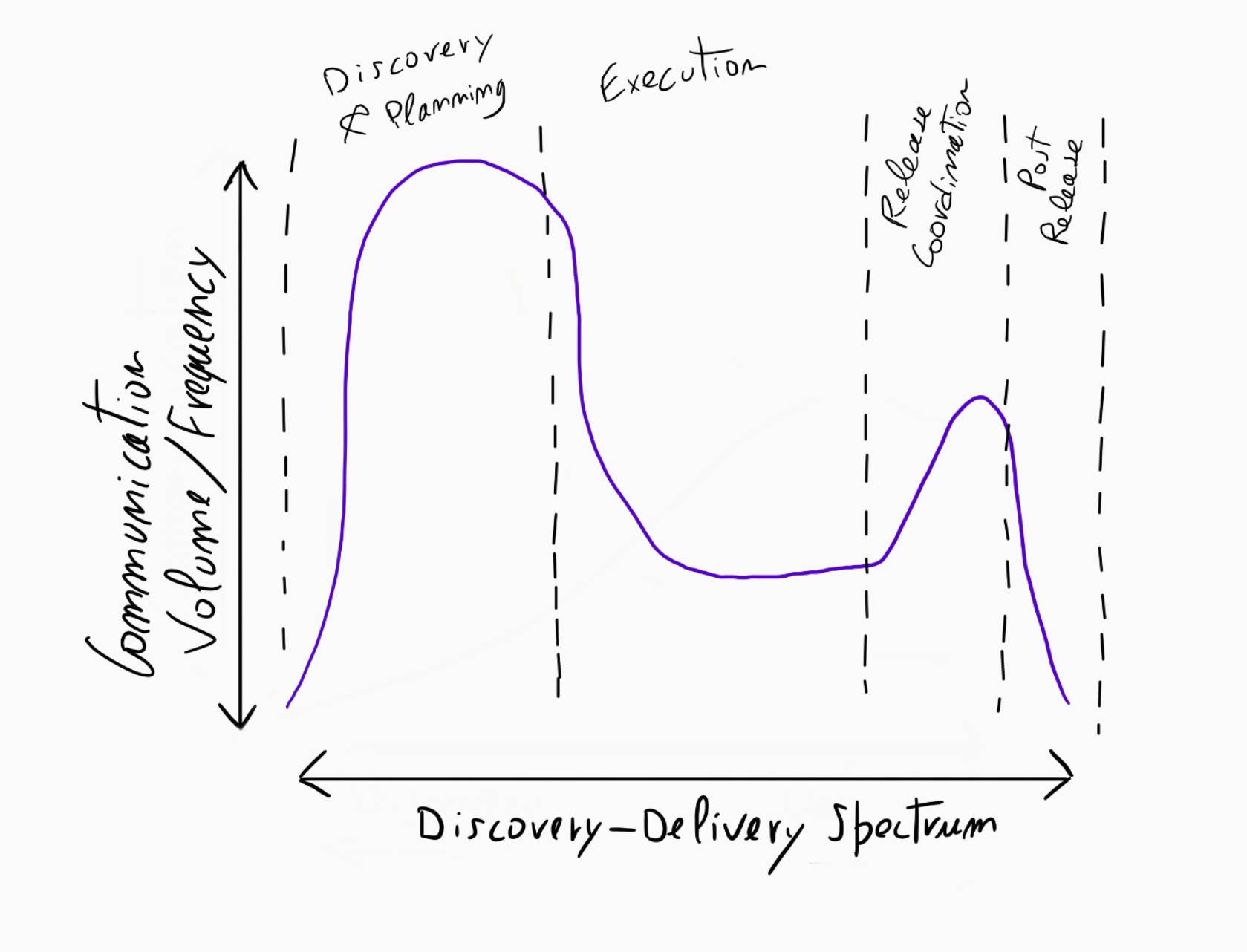

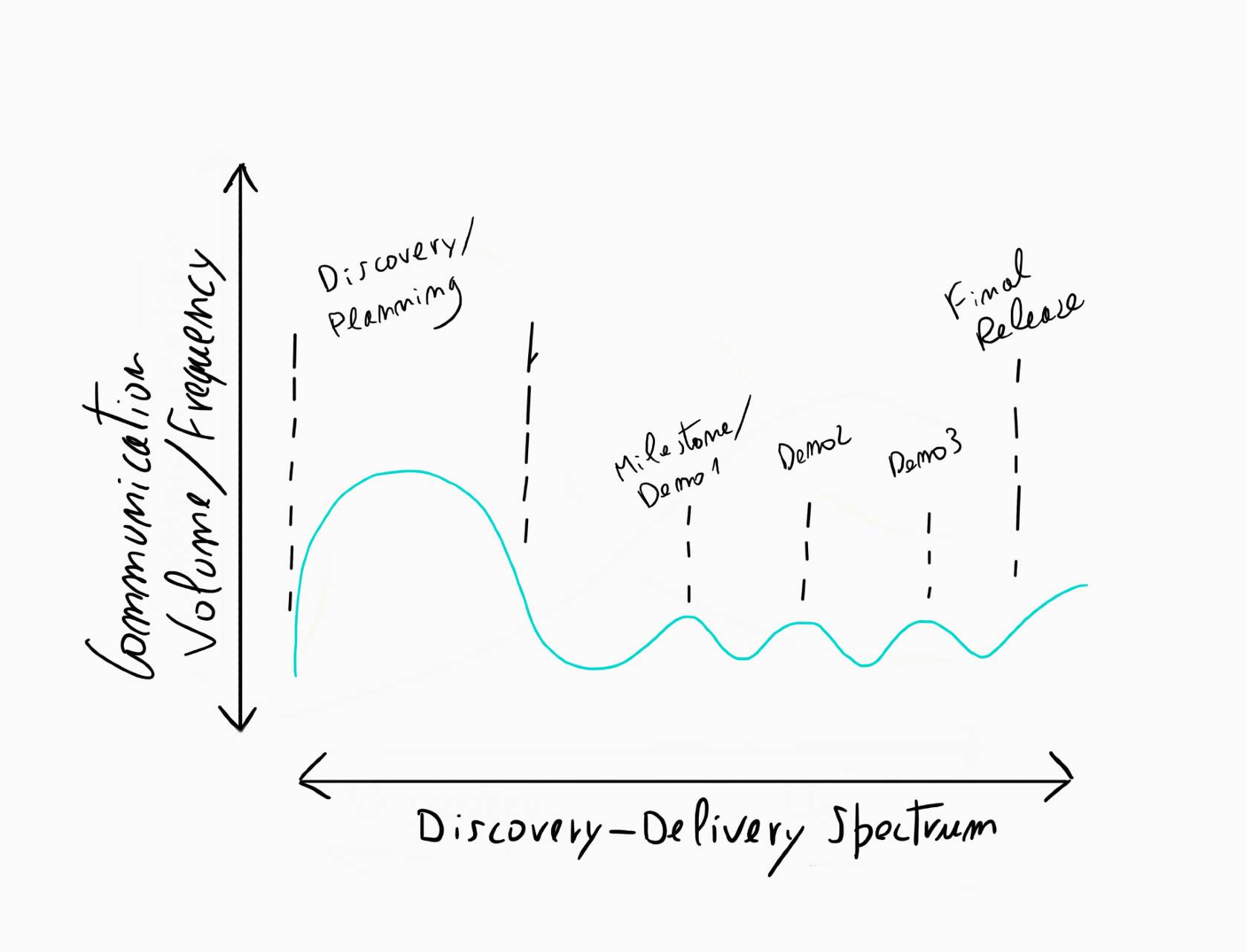

Considering this, I drew the post’s header image with three hypothetical scenarios. These thoughts acknowledge that there is not one-size-fits-all scenario or metric.

The green line

Teams start off in uncertainty and are in a mostly discovery stage with high communication volume and frequency to reduce future uncertainty as to what to deliver. They focus mainly on discovery, writing specs and planning delivery.

As things progress, the expectation is that teams should require less frequent communication as dependencies, deliveries and estimated date have been defined and planned.

Communication levels won’t ever reach zero though. As the delivery date arrives, teams might need to coordinate more, resolve last minute issues and such. It might not plateau and even pick up, but it won’t be an unmanageable stream of communication.

The yellow line

This scenario implies some late start to the discovery process – for whatever reasons. As a result teams likely won’t spend as much time planning as they should. There can be less communication happening as the depth and breadth of discovery is smaller due to less available time to juggle discovery and delivery. The may not have enough business support to do discovery so must juggle ongoing work with it.

As teams arrive closer to the release, the volume of communication might not go down much as they’ll be making up for lost ground for less discovery and delivery planning, dealing with unforeseen work and the unavoidable release hiccups.

The red line

This is where what can go wrong does go wrong: shallow discovery, poor planning, poor understanding of cross-team dependencies, lack of clarity to desired product outcomes, understaffed teams, context switch, overlapping expertise domains – pick your poison.

As teams move closer to the release date and start reintegrating their work to get it reviewed, tested and so on, things start to come up: unforeseen issues, product/design consistency issues, unaccounted scenarios, deploy hurdles, etc.

As teams continue moving forward, they require to communicate more and more to resolve all “normal” issues but also a higher than average number of issues that could have been anticipated/prevented. That, plus any other issues that may come up from other systems they maintain, customer complaints or business requests that may be urgent for whatever reason.

There’s not one single path

Are these lines representing communication volume/frequency real or even useful? Are these the only patterns? Surely no. This us just a thought exercise.

The reality is that a wide variety of things can impact this signal. It’s up to the leads to know how to interpret it in light of the characteristics of the product being built, the team and many other details.

One factor can be the main element that results in unmanageable volumes of communication. Simultaneously, an ever growing volume of communication (or at least high and not diminishing volume) doesn’t mean that any individual or combination of factors exists.

A higher volume isn’t necessarily bad – again, it depends on context. How are the teams organized? How do they communicate regularly? What does the planning and delivery phases look like?

Communication pattern for a "golden path" of discovery-delivery?

A specific SDLC may imply in a patter with larger upfront communication frequency during the discovery phase, followed by a “quieter” stage of execution, followed by an uptick due to release coordination and finally a post release stage, with hot fixes and coordinated improvements resulting from production monitoring.

Communication is more constant when doing continuous delivery.

Another pattern with higher release frequencies may likely results in a more constant/stable/manageable (yet relatively low) volume of communication, as unforeseen or unplanned work is detected and acted upon earlier.

Ultimately, the leads (and everyone) should use team communication volume and frequency as a signal that can be used to proxy team and delivery health. That and a good understanding of the team’s overall characteristics can help identify whether or not something needs closer attention.

But like any effort, the more time spent on discovery and planning, the better.