Balancing Engineering And Product Mindsets

I’m lucky to have both a background in engineering but also in marketing & management. These areas complement each other wonderfully, although sometimes it can be tough to strike the right balance between both when building products.

Delivery Starts on Discovery

This is, to me, the most fundamental notion that can impact the success of a product. If you’re any sort of product owner — founder, CEO, product manager — you’ll get the best bang for your buck by involving engineers as early as possible in the discovery stage.

“If you’re just using your engineers to code, you’re only getting about half their value.” — Marty Cagan, Inspired

Of course the quality of the feedback you get will depend on the seniority and specialization of the engineers you talk to but it also depends on their overall business savviness. In essence, you want someone that can do a balanced, comprehensive analysis of the problem to be solved.

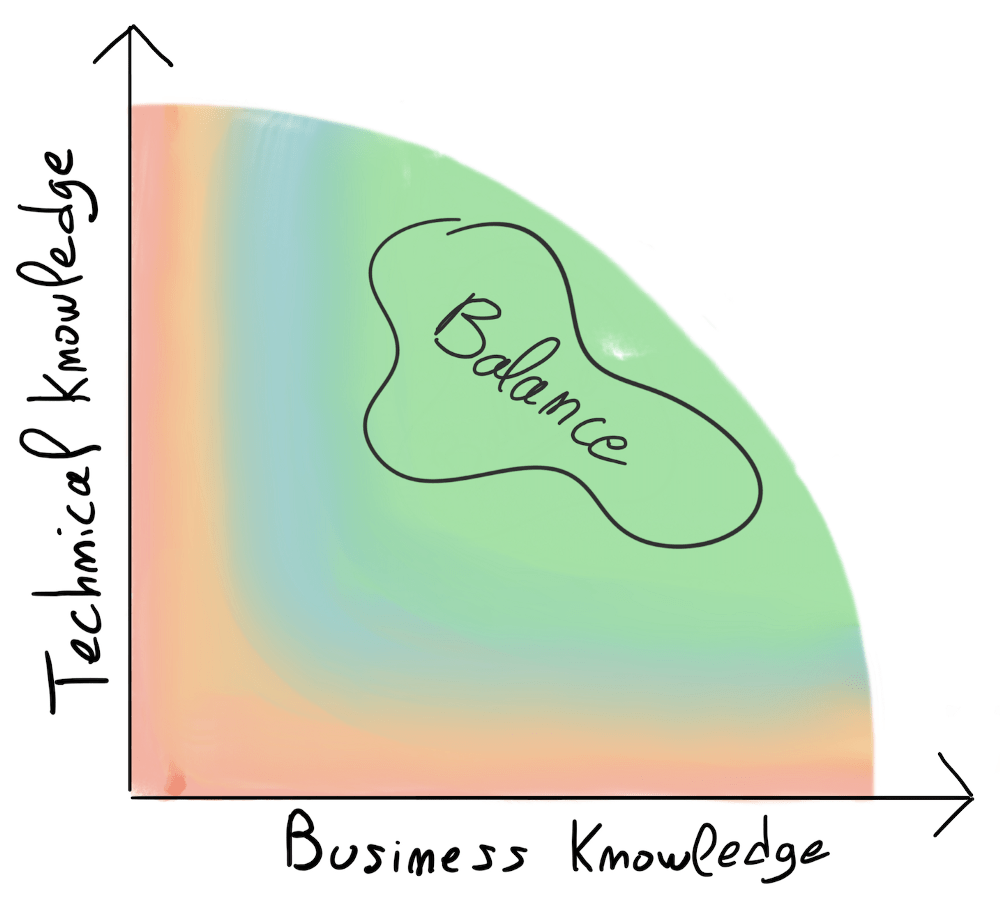

To simplify we can look at two axises: technical knowledge and business knowledge.

The sweet spot for a balanced tech lead.

Technically strong engineers with deep expertise in their stack are good at determining technical feasibility: can the technology support it? Can we scale it? What resources will it require?

But if they lack knowledge on key business aspects and nuances, or if they have no understanding of the customer and the problem to be solved, then you’re minimizing your chances of finding the best possible solution.

Conversely, someone that has a solid understanding of how the business is meant to run, that knows what customers want and how users use the product can probably come up with interesting alternatives and solutions. But if they are less experienced engineers then they may not be able to truly assess the depth or complexity of certain technical challenges and underestimate the effort required to deliver them.

Of course, this all depends on the context and scope of the product to be built as well as the skills of the team. What is true though is that engineers are usually very creative and can therefore make valuable contributions in the discovery phase of a new product or feature.

Now, as a tech lead, what you should aim for is to master the best that you can your technical stack all the while being as knowledgeable as possible about your business as a whole.

For the former that means (among other things) always being up-to-date with new techniques and industry standards and getting your hands dirty often. For the latter it means talking frequently and extensively with the product manager(s), asking for feedback from customer support and sales, diving into the available data, recurrently observing user sessions and even participating in customer interviews. Anything that can put you in the upper-right corner of that quadrant.

As an example, while working on Unbabel’s web based translation product (think of an interface along the lines of Google Translate), we realized that users had to painstakingly switch between the source and target languages they were requesting translations for.

Together with the product manager we pondered on how this experience could be enhanced. It had come to my attention that our NLP team had developed a service that could do language detection for another product. The idea was straightforward: what if we detected the source language and automatically switched the target translation on the user’s behalf so they wouldn’t have to do it manually?

I reached out to the other team’s tech lead as well as other engineers that worked directly on the service in order to ensure it could handle the load, all the while performing tests to determine that the detection success rate for each of our supported languages was acceptably high.

After validating these, I sat down with the designer to think on how we’d change the UI to support this new feature: the user would need to understand that the translation direction had changed automatically; there could be cases where our detection confidence level would be too low to perform the switch; the user could want to turn off the feature; in some cases the feature wouldn’t even be made available.

![]()

Usage of the automatic language detection Vs. mouse clicks Vs. keyboard shortcut.

After this joint effort, we incrementally released the feature to our users and observed its adoption. It wasn’t a flop but it also wasn’t the success we had hoped for. Turns out many users had perfected their workflow over time and were simply faster at completing their work that way than changing it to use the new feature (there were also other factors, such as detection latency from network roundtrips).

Nonetheless, I think it is a great example of the dynamics that can arise when engineers understand their products’ users and leverage on available systems from within their organization.

Delivery is About Managing Tradeoffs

As mentioned above, tech leads need to have a good knowledge of their technical stack but also know enough about the business, use case and customer persona in order to better emphasize with the problem. Combined, these enhance the likelihood of coming up with good solutions and anticipate issues better than non-technical people.

But more concretely, when you’re being asked to participate in a discovery phase, what is being sough from you is an assessment on the feasibility of the ideas that are being tossed around: can you and/or the team build it? How long will it take? Are there internal or external dependencies? What are the easy and hard parts of it? What is it that we don’t know we don’t know?

As the assessing engineer, you’ll be required to have some rationale to justify why one thing may or may not be doable. And for that, it’s best for you to have some ground to support your opinion.

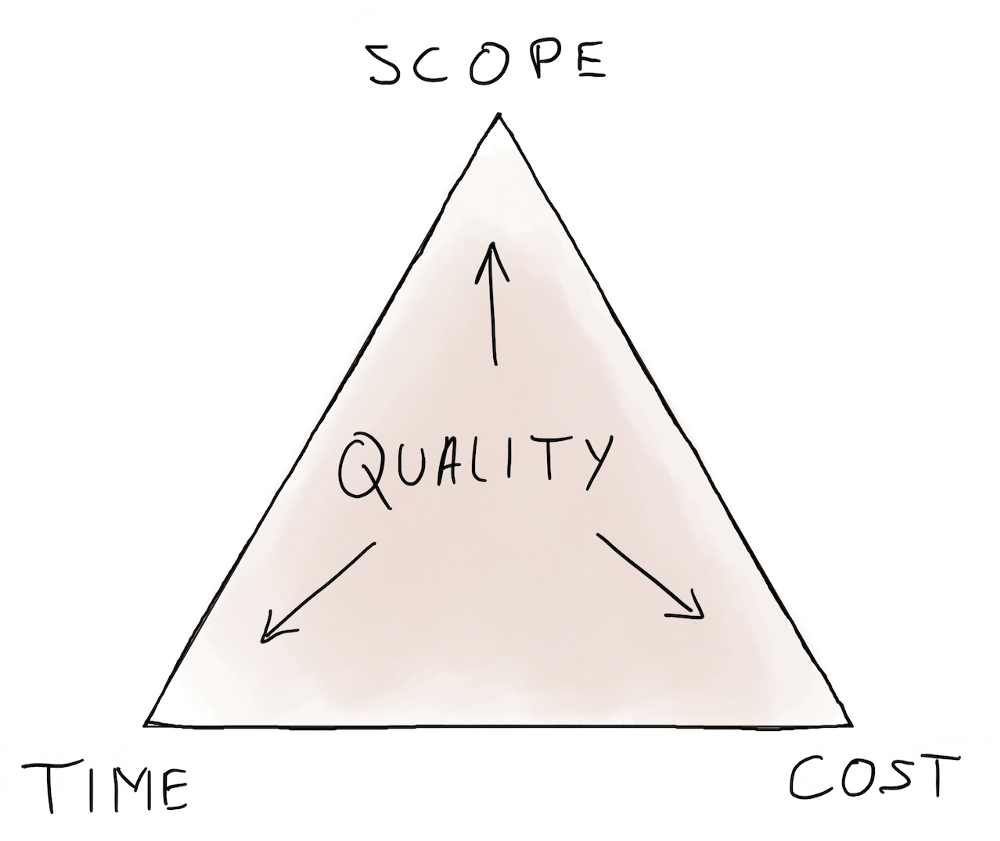

Classic constraints model of project management.

Thinking in terms of project management constraints is a great starting point.

Some people don’t like the term “project management” because of the usual process overhead that it can bring (and the word management). Rest assured, in this case we’re only interested in a framework to guide our thoughts to assess deliverability, not on which delivery methodology to use.

The constraints are scope, time and cost, with the idea being that each is interconnected and changes to one will require changes to another.

Again, tradeoffs. Your goal as the tech lead is to assess the problem and provide the best possible solution under these constraints.

Now, the interpretation of what each constraint holds and their relative importance will differ depending on the client, company, market and experience of the people you’re working with as well as your own experience and knowledge of the business.

Scope

The scope of work to be done can change depending on who you’re talking to, but as the person leading the technical implementation, you’ll need to agree on concrete things that you and your team will work on.

That can be derived from user stories. More specifically, the set of features and requirements that need to be built and delivered. From there, some may be imperative to be done while others can be secondary or pushed to another release. It really depends on the context so it’s important to agree on which ones are critical and which ones aren’t so that you know what can be shuffled around or prioritized according to the other two constraints.

What can affect scope?

Usually a combination of vague requirements description and weak change control.

The former is avoided by ensuring there’s a strong exploratory phase involving key people from product, design and engineering in order to generate good enough written requirements (user stories, documentation, architecture diagrams, etc).

Change control is, in my opinion, the hardest to tackle. A lot of scope creep originates from product demos with clients and stakeholders. Requests for new features must be handled tactfully. Stakeholders are not all equal and there are times where a sales team will agree on delivering something in order to close an important deal with a strategic client. Every case is different.

Note that it’s not only clients or sales that can change the scope. Developers with a high degree of creativity and autonomy are essential to a high-performing team but they can introduce features that add to a solution’s complexity and therefore maintainability (in this case it’s the scope’s maintainability that changes). A healthy code review culture can help mitigate these.

Coming back to the knowledge quadrant, a tech lead (and team) that is knowledgeable about the business and shares a product mindset is better prepared to understand why a new feature may be more important than another.

Time

When it comes to time constraints, we can think in terms of accumulation — like the time required by someone or a team to deliver something — and in terms of a point in time — like an agreed date (deadline) to ship a feature to any particular stakeholder.

Both are related and influence each other but one will usually determine the other. For instance, company yearly OKRs act as internal deadlines, where we’ll need to show deliverables that contribute to those. Compromises with important customers, partners or PR events also create deadlines. Finally, there can also be intra-team deadlines from when a team expects you to deliver something they depend on.

On the other hand, some things simply need time to be done no matter when the company wishes to have it delivered. In that case, it’s the development time that drives the deadline and that’s why having an idea of how long your deliverables may take is important. It helps at setting deadlines on when certain results can be achieved and provides a way to manage expectations.

For instance the sales and marketing departments may need to know those in order to plan their communication and go-to-market strategies.

Most of the time though we may have a hard deadline that can’t be missed, constraining the available time to deliver. In those cases we can “buy time” by tweaking the two other constraints. We can:

- negotiate the scope by re-prioritizing other requirements or shifting them to another release (change scope);

- add resources to the team by either hiring (change costs);

- use available technology that can speed up the delivery, such as open-source or by acquiring commercial licenses (change costs);

Which one(s) to go for depend on multiple factors: can other teams lose a resource? Do we have the cash to hire people or buy the license for a specific piece of software? Negotiating these will involve the approval of internal stakeholders so the more you understand your product’s users and the business as a whole the better you can make a compelling case to negotiate those constraints.

Finally, but not less important: when working with a team, don’t assume the time or effort to deliver something on their behalf. Involve them in the discovery phase to allow the team to better assimilate the requirements, assess the effort realistically and get skin in the game.

Cost

I like to think of direct and indirect costs.

Direct costs — those you can easily measure financially like salaries, tools or infrastructure and indirect costs — are harder to correlate with money but that can, well, cost you some way or another, like not solving the pain that customers have been complaining about for ages and instead deliver something else.

Let’s not spend much time on direct costs as they are pretty much straightforward and, as a tech lead, the decision power may not rely with you. Instead, let’s look at how technical and implementation choices can incur some form of cost to your team or organization.

For instance when determining the stack to use for a certain project or feature:

- Is my team knowledgeable enough in this stack to strike a good speed/quality balance?

- Should the need to increase the team or replace someone come, what’s the average salary for an engineer with knowledge in this stack and how readily available are these skills in the jobs marketplace?

- If the stack doesn’t scale well, will we need to spend time in changing or refactoring part of it later on? Will there be time to do so?

- Are we able to use a stack that is challenging and enticing enough for top engineers to work on to keep them engaged and stimulated?

These are some of the things to look at that can affect costs, usually by increasing the effort and time to deliver something which, ultimately, delays sales and hurts our revenue.

While conceptualizing a data visualization UI for Unbabel’s Portal, all of the above constraints had to be equated.

The challenge was to deliver an innovative and compelling experience that would allow customers to visualize and understand the whole translation layer provided by Unbabel. The product manager and designer worked closely, envisioning data flowing in real-time across information nodes with the ability to drill down on multiple areas of the interface. We also wanted it to have smooth transitions and delightful animations.

It became clear that some serious custom development would be needed to deliver this vision and we were only talking about one of the many sections of the product needed to have (we had dozens more interfaces to work on).

Something along the lines of D3.js would be the best choice in terms of versatility, customization and performance but unfortunately it has a steep learning curve. We didn’t have any frontend developer that could be fully dedicated at learning it with the required depth to achieve the desired experience.

Was it worth hiring a new resource with knowledge in dataviz that could work on this? How about hiring a freelancer to focus on it? Truth be told, we weren’t certain on the value that this interface would bring to our users. It was meant to act both as a “wow-moment” and as a way to differentiate us from others, but how much were we willing to invest in order to assess the value of this interface?

Alternatively, what chart libraries were out there that could be used to achieve the visualizations we had in mind? I researched open sourced ones but as expected they couldn’t be customized much. I ended up finding a paid solution that did provide many more charts than the classic ones and was fairly extendable. Unfortunately none could achieve precisely what we had in mind, but there were some interesting candidates.

I presented this to the product manager as a halfway compromise: we could do appealing visualizations with good performance and fairly quickly but we’d need to change the visual concepts we had in mind and we’d need to pay for a license in order to use it.

The Language Brain page showing the distribution of translations.

After experimenting and tweaking the design concepts with what the library allowed for, it was deemed that this would be the best way forward, for now. We got approval to acquire a license for it and got to work. It allowed us to deliver the interface on time while not incurring costs of hiring or shifting resources from another team. We did have to compromise on the initial experience we had in mind, but that’s how tradeoffs work.

Final Thoughts

Even though this piece is more geared towards tech people, the same roughly applies to the other mentioned roles. The idea here is that product managers, designers and tech leads must be willing to dip their toes into each other’s areas in order to be more complete professionals.

It’s easier to convey your side of the story if you know how to frame it in a way that the other party can understand.

Communicate continuously with the product manager, designer and the team as a whole. So many misunderstandings arise from assuming what was meant. Be skeptical of your interpretations. Ask questions and communicate back what you understood through hypothetical scenarios and user stories. Don’t be afraid to look foolish by asking for clarification

Finally, respectfully point out when processes or hierarchies are hindering your ability to deliver but always make sure to bring suggestions on how to improve those — people will be more receptive of your critique if you also have solutions thought out.